Greymouth Industrial Relics |

Brunner Beehive Coke Oven |

Tyneside Mine Chimney |

Relics from the town's past stood along the walkway: old coal wagons, dredge buckets, and cranes. A toolkit of telegraph poles stood on a slight rise, the top parts of each had been machined so that they resembled screwdrivers, drills and an auger.

I reached the small Erua Moana Lagoon where trawlers were moored. I took one look at them, then a long lingering look at the breakers and surf surging across the bar at the river mouth, and wondered if they only dared cross at high tide. I could see how many ships had been lost at that maelstrom of crashing waters.

Formerly The Blackball Hilton |

I did get to the museum, which told the story, through masses of photographs, of how the town became established through the coal trade. Many mines lay up the river, and initially coal was transported down to the port on barges, but when rail was introduced, it took over the role for coal transportation. The gold and coal mines in the region were covered in depth, as well as the shipping, sporting achievements, hotels, public buildings, local dignitaries, and even the day the queen and husband visited the town.

A drive up the course of the river was necessary to pick up more of the mining history of the region. My first stopping off point was Brunner. When European explorer Thomas Brunner, guided by Poutini Ngai Tahu Maori in waka/canoes, spotted the thick black seam on the far edge of the Mawhera/Grey River in 1848, little did he know that "Brunner" would become one of New Zealand's most significant coal mines.

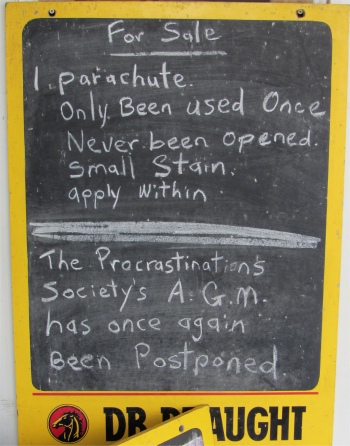

Sign Outside the Club Hotel |

An Old Mine on a Hillside |

Besides being New Zealand's most productive 19th century coal mine, it is also the site of the country's worst mining disaster where 67 miners lost their lives in a series of explosions.

My next stop was the settlement of Blackball, nestled on a plateau with the Paparoa ranges as a back drop. Blackball was founded in 1864 as a base for transient gold seekers, although the really big gold field of the area was a little further up the Grey Valley at Moonlight. Thirty years later, however, prospectors had their sights set on coal. The settlement's history had motivated me to visit.

Formerly known as Joliffetown and Moonlight Gully, Blackball was named after the Black Ball Shipping Line, which leased land in the area to mine for coal. The miners here were a revolutionary bunch, renowned for the infamous "Cribtime Strike". For years the Arbitration Court had refused to lengthen the coalmines' lunch break from 15 minutes to half an hour. In 1908, seven workers went out and refused a command to return to their jobs. When the group was fired, fellow workers joined the ten week strike. The management agreed to the longer break. The strike showed the rest of New Zealand that collective action was effective. As a result the Red Feds were established, and from them the Federation of Labour and the NZ Labour Party evolved. Blackball continued to be the centre of New Zealand radicalism and workers' militancy. In the 1913 Great Strike, Blackball miners were the last to return to work, in 1914. During the strike they had picketed miners in nearby Brunner and had burnt down the secretary of the "arbitration" (scab) union's home. In 1925 the headquarters of the Communist Party of New Zealand moved to Blackball from Wellington. Blackball had around 1200 people when the mine closed in 1964. Many left and the town was expected to gradually disappear, but it wouldn't and today around 400 people call Blackball home. The town had developed its own special wry humour, the locals even had a saying: "Blackball, the centre of the universe . . . the part where nothing moves".

A Dilapidated Roa Property |

I entered the Hilton to have a look around. The walls were covered in photos of the local mines, and showed how Brunner looked through the ages. One complete wall was devoted to the Pike River disaster which occurred on November 19th 2010. At its centre lay a large banner from the Queensland Mine Rescue Team, covered in written tributes, and surrounded by photographs of the disaster, the 29 men who lost their lives, and numerous press cuttings.

Up the West Coast from Greymouth |

Another chap walked in and the conversation stepped up in tempo. He had had a heavy session at a Karaoke do the night before, and was trying to restore his well-being with a mixture of cola and raspberry. The topic of conversation shifted to the red Volvo. "Who on earth would want to steal it anyway, it was a wreck," guffawed the barman. There was serious mirth about the disappearing red Volvo. A local who was drinking at these premises last night had left his Volvo outside at 10pm with his dogs inside, and when he left at 1am it had gone, but the dogs were found running loose. This had been the biggest crime in the small town for years, and somehow these guys found it hilarious. The unfortunate guy who owned the vehicle appeared at one point, and took some stick. He seemed to be buying something from under the shelf, which was passed over the counter to him in two opaque carrier bags. I have no idea what the transaction was, and I wasn't going to ask.

Wave Crashing Upwards at Pancake Rocks |

Sadly, the salami shop was closed on Sunday. The town's current success story was the Blackball Salami Company, which now had an annual turnover in excess of $1 million, and produced prize-winning salamis, kosher pepperoni, half a dozen types of MSG-free and gluten-free sausages (including Italian, Polish and Chorizo), various pastramis, patties and small goods.

As I ambled back to my wagon, I noticed a group of guys were busying themselves constructing an information centre relating to the Red Feds of the town. It quite amused me watching them curse as they bodged their way along. Can't say anymore or the union will be on my back.

I drove up the road that the barman had pointed out to me, where I saw the remains of an old mine. I carried on the road to its end at Roa, where a working mine still existed. Sadly many buildings in the hamlet were in a sad state of neglect.

Having had my fill of mines for the day, I retraced my steps back to Greymouth, and headed north. The coastal road north was quite spectacular, the bush clad slopes of the Paparoa Range forcing the road to skirt along the cliff tops, with horses-tails crashing into the rocky bays below. Perhaps this could be New Zealand's answer to California's Big Sur.

Blowhole at Pancake Rocks |

It was while I was at Pancake Rocks that I received a phone call from my youngest daughter, Katie. She had just started horse riding again, and was training to become a riding instructor. She was ever so pleased and excited, and I was pleased for her too. It was good to hear from her and catch up with all the family news.

I needed to get to Westport to find a campsite for the night, so I continued to wend my way north through the park. The Paparoa National Park was created in 1987, to protect a unique limestone karst environment from mining and forestry. In the interests of science, the boundaries of the park were carefully established to encompass a complete range of landscapes and ecosystems, from the granite and gneiss summits of the Paparoa Range, inlaid with limestone, down through rivers, sinkholes and caves to the layered rock formations of Punakaiki. Glacial action in the past had produced sharp ridges, steep cliffs, and cirques, and many of the deeply incised rivers and streams had glaciated forms.

The mild climate and fertile soils, coupled with an annual rainfall of over 5m, supported a wide variety of native plant life. Indeed the park was the overlapping point between subtropical and cool climate trees. Nikau palm and northern rata trees emerged above the forest canopy, and cabbage trees gave the lowland rainforest a lush, Pacific feeling. Further up, silver beech forest merged with sub alpine shrubs. Higher still, daisies and gentians provided colour among the alpine tussocks. Some plants were unique to the area, suggesting that it was a botanic refuge during the ice ages.

The bird life in the national park was also remarkable for its diversity as well as for density. Several species such as tui, bellbird, kaka, New Zealand pigeon and parakeets migrated from winter habitat in the lower forests to summer habitats in the upland forests. The Westland Petrel/titi colony bred south of the Punakaiki River, and stayed mostly out at sea, but during the breeding season they could be seen flying to and from the colony at dusk and dawn. Great Spotted Kiwi combed the forest by night.

My route continued to hug the craggy coast as I headed to my most northern destination on the West Coast, the mining communities around Westport. Just 30km short of Westport lay the historic gold mining township of Charleston. During the 1860s gold rush, this was a boomtown and home to 18,000 people. Today, it was hard to detect an afterglow from those heady days.

The drive into Westport was straightforward, and I picked up a campsite with no difficulty. The lady at the desk explained to me that tomorrow was a public holiday, she wasn't exactly sure what for, but it was a centennial celebration of sorts. She cursed such things, saying they were a waste of time. It may cut my options for the day too.