The Chasm from Above |

In the communal kitchen where I was sorting out my deluxe breakfast of cereal and coffee, I bumped into Tony and his wife, who had been in the next pitch to me at Geraldine. The world is indeed small. He had been to Milford Sound the previous day and was off to Invercargill today, and then the Catlins. Who else would I meet I wondered.

The Mitre Almost Hidden in Rain |

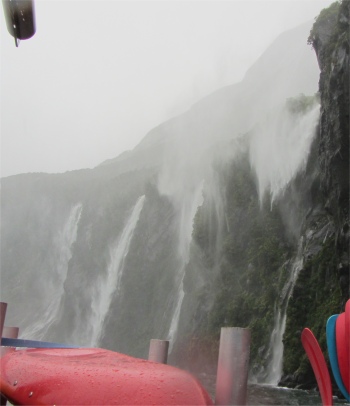

A Lacework of Waterfalls |

55 Knot Winds at This Narrow Point |

Towards the head of the valley, I started to climb up to the Divide. The 532m high Divide was the lowest east-west crossing of the Southern Alps. There wasn't much here apart from a car park with toilets, and a large walker's shelter. This marked the start/finish point of the Routeburn, Greenstone and Caples tracks. Declining the walking opportunities here, I headed on, descending partly into the Hollyford River Valley, before veering west along the main road towards the huge glacial cirque of the Gertrude Valley, the source of the Hollyford.

Waterfalls Being Blown Back up the Cliff |

Ship Venturing Near a Set of Falls |

Water Water Everywhere |

A short drive brought me down to the silky-black waters of Milford Sound. It ran 15km inland from the Tasman Sea and was surrounded by sheer rock faces that rose 1200m or more on either side. Across the waters in front of me, occasionally through the banks of rain, appearing as a grey looming glaciated mass, the sheer-sided 1692m slab of rock called Mitre Peak dominated the sound. Other notable worthies were the Elephant at 1517m and Lion Mountain, 1302m, all obscured by the curtain of rain. Lush rain forests clung precariously to these cliffs, with the odd gap where gravity had won the day and torn vast chunks of the vegetation away from the rocky faces and cast it into the watery wastes far below.

The grand scale of Milford Sound was best appreciated on one of the many boat cruises on offer. I had picked out a suitable cruise whilst in Manapouri, the nature cruise aboard the Milford Wanderer. For some odd reason, the car park at Milford Sound is a 10 minute walk from the cruise departure point. After just 100m of this walk, I was totally soaked from my hips down; just dandy.

Bowen Falls |

The fiord sported two permanent waterfalls all year round: Lady Bowen Falls (173m) and Stirling Falls (160m). During todays heavy rain however, a lacework of many hundreds of temporary waterfalls could be seen running down the steep sided rock faces that lined the fiord. They were fed by rain water drenched moss and would last a few days at most once the rain stopped. Heavy rainfall was a regular feature of this region with up to seven metres being experienced in some years. There was an upside however. On the 182 rainy days of every year, the whole landscape would take on a brooding, mystical quality and the sheer granite walls burst out into hundreds of spectacular waterfalls. Whole mountains came alive with waterspouts and cascades, creating a very dramatic photogenic "mood" scene.

Kea Trying to Break Into My Car |

Our craft slowly motored over the turbulent waters which were populated by white seals, penguins and dolphin. On a calm day the nature cruise would have been busy spotting all this marine life. Today, just a couple of seals and their pups were spotted on a large rock. The boat hugged the cliffs, occasionally taking a mist filled shower from one of the vertical torrents of water, and I soon found we were crossing the sill of the fiord and our craft was being pounded by the choppy swells coming in from the Tasman Sea, with great spumes of salt water adding to the experience. From here it became obvious why it took 50 years from Cook's first sail past the fiord before anyone actually found there was a fiord at all. Due to a kink in the fiord at the entrance, it appeared to be just a large bay. After a few hilarious soakings, we resumed our trip back up the fiord, and just soaked up the majesty and scale of our surroundings, or what we could see of it. I was mesmerised by the water somersaulting off ledges of glistening, dark bedrock, bursting into spray; the whole mountainside an intricate tumbling aquatic lacework. Awesome was the only superlative that did justice to Milford Sound, whose towering granite walls would simply dwarf cruise liners, and left human impacts on the landscape looking like a world in miniature.

The original impacts in the area were created by the first settlers at Milford: Donald Sutherland, J. McKay, and J. Malcolm who, in 1877-80 built permanent huts both at the head of the fiord and at Anita Bay near the entrance. At first they were interested in deposits of asbestos and greenstone at Anita Bay, but in later years Sutherland married and settled down in the homestead at the head of the fiord.

As we passed close to Stirling Falls, the captain announced, "Now ladies, we are going to get close up to these falls. The legend has it that the spray from them landing on a woman's face would make her look 10 years younger." A story of course, but I was amazed how 90% of the women trooped out in the rain for a good soaking in the spray. No comment.

All too soon we were back to our departure point. The cruise had been a total contrast from my Doubtful Sound experience. Despite being soaked through for the entire trip, I was glad I'd seen this rugged land in its rawest form; it added to the Kiwi experience.