Soon I was heading down the 93 towards Lake Louise, with very little traffic; all commercial vehicles were banned from this route. The road would take me through the Icefields Parkway through remote, high elevation terrain. If you enjoy chocolate box scenes, this is the place for you; mile upon mile of snow-capped mountains, glaciers, green rivers and blue lakes.

The Icefields Parway was expressly designed to dramatise the incredible landscape, and runs below the highest mountains in the Canadian Rockies. Following the valleys of five rivers, the road angles southeasterly along the eastern flank of the Continental Divide connecting Jasper and Banff National Parks. Glaciers, lakes and waterfalls are abundant along the route, as are interpretive lookouts that explain the natural and human history of the area. Driving the route also exposes visitors to the reality of climate change as glaciers throughout the parkway's entire length are in rapid retreat. The parkway was begun during the great depression as a public works project and was opened in 1940. Though it traverses some of the most spectacular scenery in North America, its relatively gentle grades make it popular with cyclists. I saw scores, though often their heavy loads often forced them to walk up some of the hills. Officially the parkway encompasses the entire length from Jasper to Banff, a total of 197 miles. The 144 mile stretch north of Lake Louise is the most scenic and famous.

I did come across some wildlife too. As I rounded a bend I noticed a few cars pulled up on the side, then I saw why. About 20m in front of me a black bear was sauntering across the road, then disappeared down an embankment. Sadly I had no time to get a snap of him. 20 miles further on I saw another bear gallop across the road about 200m ahead of me. He would have been long gone into the forest by the time I pulled up. At times I would come across cars crawling along the hard shoulder, obviously they had spotted some creature in the forest and were stalking it with cameras at the ready.

Athabasca Glacier |

Tevan, Jody and Tace |

While I was taking all this in, a young couple reached the viewing fence, and with their six month old baby acting as an ice-breaker, we soon got chatting. Their names: Jody, Tace and baby Tevan. Jody seemed to have a passion for history and was envious of the English heritage. We talked of his travels to New Zealand and how he would love to visit Britain. He was a welder by profession, and he and his family lived in Brooks, Alberta; the plains area he referred it as. We watched the stream emanating from the bottom of the glacier, and he said that it would eventually pass through his home town where it would be used to irrigate the prairies. We discussed my trip, and since he was 'local', I sought his advice on getting from Banff to St. Mary in Montana. When I planned the trip my route was to bypass Calgary and drop down Highway 2 towards Montana. Jenny and Paul, who I met at Nairn Falls, suggested dropping down the Kootenay region, admitably more scenic, but I reckoned that would put me on the wrong side of the Continental Divide for the "Going to the Sun Road". Jody suggested turning off before Calgary and head down the Cowboy Trail Highway 22. This would still be prairie country and allow a chance to see this aspect of the landscape. I thought it was a good idea. He wisely pointed out that I should make a judicious choice of Canada/USA border crossing. The most obvious one, he pointed out, was a small one-man crossing point, and if the official had left off for the day, your option would be to turn back or wait.

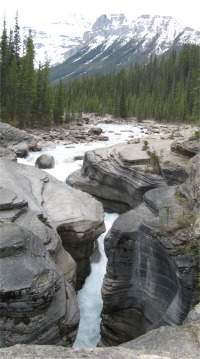

Mistaya Canyon |

Baby Tevan was a bonny, happy, easy going little fellow, already possessing an inquisitive mind; he had five cousins to spur him on. I talked about my grandson, Oliver, who is a little older than him. All-in-all, they were a really nice, friendly, generous, happy family and I enjoyed my brief time in their company. I gave Tevan a wee cuddle before we parted our ways. As I drove on, I must admit I became a bit misty eyed thinking about my grandson.

Road Closure |

In 1807, David Thompson followed in their footsteps when he crossed the range to establish Kootenae House, the first trading post on the Columbia River. For the next four years, the pass served as a portal to a succession of new North West Company posts. The pass was named after Joseph Howse who followed this route in 1810 to establish a competing Hudson's Bay Company post.

I continued my journey down to Peyto Lake. Here, the car park had been cleared of snow, the remains of which formed battlements around the parked vehicles. I took the trail up to the observation point overlooking the lake. I was high up, and a fair percentage of the trail involved trudging through snow, but it was worth the climb. I suddenly burst out upon a birds-eye view of the glacier fed Peyto Lake far below. It was stunningly blue, as if it were a lake of copper sulphate solution. Half of it was iced over, but even that appeared blue. The gently falling snow added to the effect that you were with the Gods. The blueness arose from the silt washed down from the glacier, most of which sank, but fine, floury stone particles remained suspended in the water, and it was the suspension that reflected green and blue light.

Bow Lake |

I made the last leg of the day down to Lake Louise. The village lay at the confluence of the Bow and Pipestone Rivers. There wasn't a great deal in the village, but it did have an excellent and helpful information centre. It even had all the weather information you would want for the next week. The geology of the area made a fascinating read. A 25 min. video gave a very informative account of how tourism has had an environmental impact and efforts being undertaken to offset that. Lake Louise is a very popular place. The emerald hues and glacial backdrops of Lake Louise have wowed visitors since the 1890s. Known by the Stoney Nakoda First Nations as "Lake of the Little Fishes", Lake Louise was named in 1884 in honour of Princess Louise Caroline Alberta, daughter of Queen Victoria. The impact on how the sheer number of summer tourists affected wildlife, and how overpasses and underpasses were being built for animals to follow their normal passages across the area, were all very interesting. It was also made very clear that the area is a prime habitat for grisly bears. It had been decreed that certain trails must follow the rule of four for hikers. In essence four or more hikers make a lot of noise to warn off bears and would be safer than individual hikers.

In the small square of the village, there was an art gallery, and I couldn't resist going in. The owner mentioned it was all Aboriginal art. I had come across the term Aboriginal at Mistaya Canyon, and I was perplexed about its usage here. Perhaps I was just thick. I asked the owner, and he quite rightly pointed out that an aborigine is an original inhabitant of a country or region. In the 1970s when Canada cut its ties with the English sovereignty, the Canadian government had decided to adopt the word Natives, but ran into difficulty with that because anybody born in Canada was considered to be a native of Canada. After a lengthy process they chose the politically correct term, First Nations people. We discussed art at length and whether up and coming art should be judged as of now or perhaps in the perspective of time. His view was the latter; good art will reveal itself in a hundred years or so. I could not help but feel he was contradicting himself at times, since he considered he could spot good art now. After a while I felt as though I was being lectured to; he did give lectures in art. I made my excuses and left.

I located a campsite near the village, again enormous, but the special feature of this site was an electric fence to keep the wildlife out, or us in. I cooked and as I sat eating I could feel the chill starting to creep inside me. The village was at an altitude of 1540m, about 100m below the snow line.